|

|

|

|

|

|

|

News & Views item - June 2007 |

![]() India's Prime Minister Calls for the Nation to Have 30 World-Class

Universities. (June 23, 2007)

India's Prime Minister Calls for the Nation to Have 30 World-Class

Universities. (June 23, 2007)

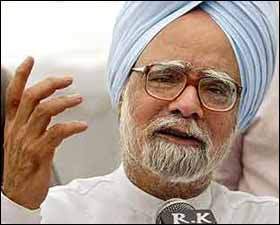

Indian

Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh addressing faculty and students of the

University of Mumbai on the occasion of its 150th anniversary

has called for 30 world-class universities to be established across his

nation.

Indian

Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh addressing faculty and students of the

University of Mumbai on the occasion of its 150th anniversary

has called for 30 world-class universities to be established across his

nation.

Dr. Singh is an economist by training having obtained his undergraduate (1952) and a master's degree (1954) from Panjab University, an undergraduate degree (1957) from Cambridge University (St. John's College) and a PhD (1962) from Oxford University (Nuffield College).

Before becoming prime minister, he served as the finance minister and is credited with transforming India's economy in the early 90s, during its financial crisis.

Dr Singh told his University of Mumbai audience: "If we need to capitalize on our latent human potential, we need a quantum leap in our approach to higher education. We need to revamp the higher education system so that it walks on the two legs of access and excellence," and went on to say that there was a need for a massive expansion of higher education opportunities to all classes of society and to all regions of the country, "This is the only way that the lamp of knowledge can be taken to every door. We need to also upgrade the quality of the higher educational institutions so that they work on the frontiers of knowledge, harnessing its immense capabilities for our common societal benefit. The higher education system must grow on these two pillars if it is to fulfill its role in nation building."

He then went on to caution: "While we do have much to be proud of, we also have a long distance to travel in the field of higher education and research in India to attain world standards. We are at an important cusp in our developmental trajectory. We are at a point when the dynamics of our population growth can catapult us into a prolonged cycle of rapid economic growth - growth which can be the basis for eradication of the ancient scourges poverty, illiteracy, ignorance and disease."

And he pointed to the fact that around 10% of the relevant age-group is enrolled in any institute of higher education - as compared to 40-50% in most developed economies.

Compounding the problem is the fact that "Almost two-thirds of our universities and 90% of our colleges are rated as below average on quality parameters. And most importantly, there is a nagging fear that university curricula are not synchronized with employment needs."

Then the one-time professor of economics outlined his proposals: "A key recommendation of the Knowledge Commission is that we must undertake a massive expansion of higher education in our country. The Commission believes that by 2015, India should attain a gross enrolment ratio of at least 15% if we are to be in line with most modern societies. Such a quantum jump in our university system has to be well planned and well funded. We need, not just financial and physical resources, but also human resources. We have to universalize our secondary school system so that we generate enough good quality students who can then seek admission to higher education. We need more and better teachers and better facilities."

To facilitate the "quantum leap" Dr Singh then announced his intention to establish 30 new central universities across the country.

As distinct from universities run by Indian state governments, a central

university is normally set up under an act of parliament and receives

funding from the central government and is governed by the University

Grants Commission, the nodal body for higher education, in terms of course

curricula.

According to the ministry of human resource development, there are at

present 18 central universities.

Dr Singh then directed some harsh criticism toward the states: "The quality of governance of many state educational institutions is a cause for concern. I am concerned that in many states, university appointments, including that of the Vice-Chancellor, have been politicised and have become subject to caste and communal considerations. There are complaints of favouritism and corruption. This is not as it should be. We should free university appointments from unnecessary interventions on the part of governments and must promote autonomy and accountability. I urge states to pay greater attention to this aspect. After all, a dysfunctional education system can only produce dysfunctional citizens."

And he concluded by telling his Mumbai University listeners:

The work on the modalities for setting up these [central universities] has begun and the Ministry of Human Resource Development, the UGC and the Planning Commission are working to operationalise this in the next 2-3 months. This expansion is going to be a landmark in expanding access to high quality education across the country.

Access to higher education has two dimensions of which expansion of supply is only one. If the latent demand for higher education is to be converted to a real one, we need to consider ways of improving the financial resources of aspiring students as well. While our Government has taken several steps to expand the scholarships available to students, including SCs(1), STs(2) and minorities, we need a much larger national programme so that no one who wants to pursue further education is denied this opportunity for lack of resources.

Our university system is, in many parts, in a state of disrepair. We need better facilities, more and better teachers, a flexible approach to curriculum development to make it more relevant, including more effective pedagogical and learning methods and more meaningful evaluation systems.

(1) Scheduled castes, the disadvantaged castes of India commonly known as Dalits.

(2) Scheduled tribes, the disadvantaged tribes of India commonly known as Adivasi (a substantial indigenous minority of the population of India).