decline

of interest in mathematics and the sciences in the school population. The two overarching concerns are

defining the reasons and determining how to reverse the decline. In his recent

editorial in Science

decline

of interest in mathematics and the sciences in the school population. The two overarching concerns are

defining the reasons and determining how to reverse the decline. In his recent

editorial in Science

In reviewing how the Institute could best utilize its resources to make a useful contribution to address the crisis HHMI's put money where its President's concerns are. The Institute announced at the end of August last year a competition to find 20 "outstanding teacher-scholars". Now each of the winners has been awarded US$1 million for the next four years "to develop new modes of science teaching." In addition there is an increasing emphasis, though the resources are relatively small, by the US National Science Foundation as well as a number of individual US research universities to foster mentored undergraduate research similar to honours degrees awarded by Australian universities.

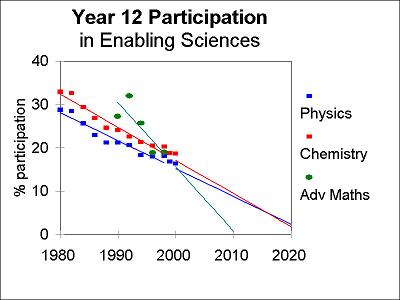

The waning interest of Australian Secondary Students in the enabling sciences (provided by John O'Connor, University of Newcastle).

The approaches that will be developed by HHMI's 20 scholar-teachers are to be disseminated broadly, for example through Website- and/or DVD-based resources. Perhaps Australia's Minister for Education, Science and Training will encourage those in his charge to monitor the progress of HHMI's initiative and determine the relevance to the Australian scene. It is clear that Cech embraces the proposition that to produce "qualified K-12 science teachers" requires good math and science departments and such departments are the result of a nexus of good teaching and good research.

Which brings us to the matter of what defines a science department of high quality, the sort from which a scholar-teacher worth a US$1 million investment can be drawn. The development of a high quality scientific department takes many years, in general, because only scientists of high quality are able to put together a department of high quality. When a prominent scientist leaves a university department, for example to move overseas double damage is caused, because mediocrity is self-perpetuating. In the academic world of Western research universities, the quality of the academic faculty whether it be in the humanities, social sciences, hard sciences, medicine, or technology and engineering, is determined primarily in scientific achievements. This measure is closely related to the quality of teaching. Primarily it is the quality of the subject matter taught and the intellectual power the lecturer presents to students. And as Cech emphasises, what needs to be fostered is developing a productive amalgam between discovery and the student. The quality of presentation is certainly of great importance but it is secondary to the quality of the subject matter and the thought processes the lecturer presents. Scientific research is an indispensable and inseparable part of the best teaching. A teacher who is not engaged in research has a reduced incentive to keep abreast of the rapid developments of the science or technology in his field. And one of the essentials is interacting with ones peers. If that contact with scientific reality and progress is severed, a department decays; the quality of its research and teaching will become increasingly substandard.

To date there is little indication

that the Federal Government understands, let alone accepts, the necessity for

rebuilding the infrastructure of our research universities so that

revitalised, they would provide the means and the will to produce a next

generation of outstanding Australian scientists, well qualified and enthusiastic

science and maths teachers for K-12 students and as a result,

Today Alex

Reisner

The Funneled Web