|

Editorial-18 August 2004 |

|

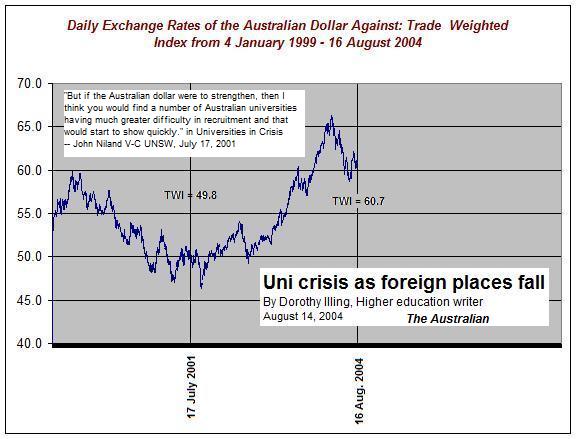

The Trade Weighted Index, Foreign Student Enrollments and a Vice-Chancellor's Prediction |

On July 17, 2001, John Niland, then Vice Chancellor of The University of New South Wales spoke to the Senate Employment, Workplace Relations, Small Business and Education References Committee. The committee had been charged with determining, "The capacity of public universities to meet Australia's higher education needs..."

Professor Niland was one of six vice-chancellors who made presentations to the committee that day (Gavin Brown, Sydney; Ian Chubb, ANU; Mary O'Kane, Adelaide; Janice Reid, Western Sydney; Deryck Schreuder, Western Australia and John Niland, UNSW).

The final 428 page report, Universities in Crisis, was released in September 2001 and had almost no impact on the Coalition government's treatment of Australia's universities -- after all the government had only a minority representation on the committee. Perhaps Senator Carr the current shadow minister for Innovation, Industry, Science & Research and a member of the committee will use the report to help develop Labor's forthcoming research policy, and will include such matters as "The capacity of public universities to meet Australia's higher education needs" in his discussions with Mr Latham and other ranking members of the shadow cabinet.

What is clear from the minority report put in by the Government Senators was their complacency and their belief that there was an over reliance on government funding for Australia's public universities.

Toward the end of his submission Professor Niland had this to say to the committee members:

Australian universities have, as I said earlier, done a remarkable job in promoting the recruitment of international students. It is to our great advantage that we continue the tradition of the Colombo Plan, and for years ahead we will have graduates of Australian universities serving in governments and ministries in the region and offshore. But a lot of our ability to sustain what we do is based on the weakness of the Australian dollar [our emphasis]. Just one observation I would like to leave with you is that, if the Australian dollar recovers to the point that a number of analysts are beginning to forecast that it will, then I believe that will be a major issue that we have to encounter, because so far whatever press has occurred has been muted -- in its advantage to the Canadians, the Brits and others who are looking to recruit -- by the weakness of the Australian dollar. But if the Australian dollar were to strengthen, then I think you would find a number of Australian universities having much greater difficulty in recruitment and that would start to show quickly. There is no issue in our underlying budgetary well being that could change so quickly as the enrolment of international students from one year to the next. That is where I think our greatest risk lies.

Which brings us to Dorothy Illing's article in this past Saturday's Australian, "Uni crisis as foreign places fall".

Applications from overseas students wanting to study at Australian institutions fell 10 per cent in the first six months of this year compared with the same period last year.

Fees from overseas students are the biggest single source of private revenue for universities, making up 13 per cent, or $1.4 billion, of their total income last year.

As their proportion of government funding declines, universities have become aggressive in their recruitment of Australian and foreign fee-paying students to plug the gap.

But increased competition from other countries in a number of key markets, a rise in the Australian dollar, the SARS scare and higher fees have dampened demand.

In particular, Canada, Britain, the United States and New Zealand have been actively recruiting in Australia's established markets in southeast Asia.

The slide has been exacerbated by countries such as China, Malaysia and Singapore building up their own education export industries.

Now a spokesman for federal Education, Science and Training Minister Brendan Nelson has told Ms Illing that concerns had been raised about the downturn in applications with him. She quotes the spokesman in today's Australian, "This downturn is not, however, reflected in [Australian Education International's] current market indicators, which continue to show a steady growth in higher education international student enrolments [12.6 per cent] and commencements [7.9 per cent]."

Just exactly how that statement should be interpreted is something of a mystery as Illing also reports:

Wollongong University's vice-principal, international, James Langridge said the so-called crisis at [their international marketing and recruitment arm, IDP Education Australia] was mirroring what was happening in universities. International applications into pathway programs at Wollongong were down 30 per cent on last year. "The only other time we have had an event like this was in the Asian crisis in the late '90s, but then we knew why," he said of the downturn.

Deakin University's pro vice-chancellor (international) Eric Meadows said while his university's international numbers were on target, this was the first "serious downturn" since 1985.

Returning to the topic in hand, perhaps we ought to note in passing that prior to becoming UNSW's Vice-Chancellor Professor Niland was Head of the School of Economics, Dean of the Faculty of Commerce and Economics and the University's Foundation Professor of Industrial Relations. When he told the Senate committee beware dependence on the fluctuating dollar, it would appear he probably knew whereof he spoke.

After a short excursion into the matter of a universities' ombudsman, it was Senator Brandis' (Lib. Qld) turn to cross examine (Brandis is a barrister by training).

Senator Brandis -- Can I put it to you that, unless one takes what I would call a socialist view that 100 per cent of university funding should come from public sources, as a matter of logic there is no perfect level at which the contribution of public funding ceases and funding from other sources is contributed.

Prof. Niland --Well, Senator, I am generally in line with that proposition, and that was the basis from which I was going to prepare my answer.

Senator Brandis -- Sorry. Please go on.

Prof. Niland -- My answer is this: there is no incontrovertible formula that will produce the right answer on public funding for universities, any more than there is on public funding for the judicial system, for welfare, for hospitals, for defence and so on. So therefore we need to have some regard to standards and benchmarks that emerge internationally. For universities, that is a particularly important reference point, given our growing internationalisation and our growing engagement with a globalised world. If globalisation is essentially the democratisation of information, knowledge, investment—all of that—through e-technology, then universities are at the heart of it, and Australia had better be very alert to the challenges that its universities are going to face from that international competition and international environment. Therefore what occurs in OECD countries is, I believe, particularly relevant to the judgment that governments would make about how much to assign to universities. While that itself is not an absolute or perfect answer, if we in fact are slipping down the OECD scale in terms of the proportion of GDP assigned to universities or in terms of the balance by OECD standards between government and private funding, then that to me is an a priori source of concern. We have, I believe, a pretty deep a priori source of concern in this country because that is exactly what is happening to us.

Senator Brandis -- I understand the proposition but can I meet it by saying this to you: it seems to me that of the potential sources of revenue for universities, the least explored in this country is funding from private and commercial sources. It has been a matter of disappointment to me in these hearings to hear a number of witnesses from universities focus the debate on the question of public funding. They limit their frame of reference by focusing the debate on one source of funding, rather than asking the broader question about funding at large and how more money—not less—can be secured for universities in Australia from all potential sources. Perhaps they should be exploring at the frontier some of the sources that have not sufficiently been appreciated in Australian higher education in the past. Would you like to comment on that?

Prof. Niland -- I think that this exchange between you and me helps us focus on one of the most critical -- if not the most critical -- policy issues that universities in this country face. It can really be reduced to a very simple proposition in my set of values: we need an understanding, an arrangement, a contract -- a deal, if you like -- between universities and government. The deal would be something along the lines of the government saying to universities, ‘Okay, we are prepared to guarantee or drive toward assigning to you a certain proportion of GDP or some other relevant reference point. You can be assured that that won’t go away, but your side of the deal is that you have to very actively drive on beyond that to generate private sources of funding.’ Frankly, one of the concerns that exists within universities is that for each dollar we earn through the front door, government takes a dollar out the back door. If we could only cut through that and arrive at some bipartisan based compact between the university sector and government, built on that understanding, then I think we would have the best of both worlds. I am certainly not arguing with both hands outstretched that our only solution is public funding. Indeed, that is a forlorn argument and it will lead us nowhere. On the other hand, if you have this fear of front door/back door balancing, then that is a pretty forlorn outcome too.

It looks like Professor Niland got out while the getting was good. Whatever the reasons, in July 2002, following the completion of a ten year term as Vice-Chancellor and President of UNSW, he became Professor Emeritus at UNSW and an Independent Non-Executive Director of the Macquarie Bank.

Anyone observing Niland speaking to his submission before the committee members would have heard him trying to get the points across that to base the well being of the higher education sector on an over reliance of overseas student fees was courting disaster and unless the quality of the 'products' placed on offer was competitive by world standards, once the value of the Australian dollar rose income would decline.

Good universities attract good students. The best universities attract the best students who in turn improve those universities and the common wealth. Unfortunately for Australia that doesn't occur within a three year election cycle.

In any case Professor Niland's hopes of a compact "an understanding, an arrangement, a contract -- a deal, if you like -- between universities and government," are yet to be realised. That deal "would be something along the lines of the government saying to universities, 'Okay, we are prepared to guarantee or drive toward assigning to you a certain proportion of GDP or some other relevant reference point. You can be assured that that won’t go away, but your side of the deal is that you have to very actively drive on beyond that to generate private sources of funding,'"

Ah, there's nothing quite like the naiveté of academics.

Alex Reisner

The Funneled Web