|

|

|

|

|

|

|

News & Views item - August 2010 |

![]() Speak

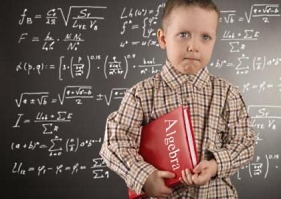

Some Algebra for the Ladies, Baram. (August 13,

2010)

Speak

Some Algebra for the Ladies, Baram. (August 13,

2010)

In

the days when Harold Ross was editor of the New Yorker, one of its

celebrated cartoons depicted a group of women in a suburban New York living room

seated at several tables playing Mahjong when the young son of the hostess

arrives back from school. To impress her guests the mother invites Baram to

"Speak some algebra for the ladies".

In

the days when Harold Ross was editor of the New Yorker, one of its

celebrated cartoons depicted a group of women in a suburban New York living room

seated at several tables playing Mahjong when the young son of the hostess

arrives back from school. To impress her guests the mother invites Baram to

"Speak some algebra for the ladies".

In the April 23rd issue of Science Bruce Alberts' editorial addresses the problem that presenting science subjects in the schools is being hampered in part by the language employed which is devoid of narrative, thereby making it difficult for the students to comprehend. In addition Catherine Snow in a Perspective finds that: "A major challenge to students learning science is the academic language in which science is written. Academic language is designed to be concise, precise, and authoritative. To achieve these goals, it uses sophisticated words and complex grammatical constructions that can disrupt reading comprehension and block learning. Students need help in learning academic vocabulary and how to process academic language if they are to become independent learners of science."

In consequence Science received a number of letters of which it published a half dozen. Here we refer three.

Calfee and Bruning make the point that while they: "heartily agree with the viewpoint that science and literacy instruction should be integrated... [their] deep concern, however, is with the significant barriers to integrating science and literacy instruction that presently exist, especially at the elementary level. Classroom practices in most elementary schools... emphasize reading and basic math [and] currently leave virtually no time for science instruction. In addition, many elementary teachers are poorly prepared and uneasy about teaching science. Until these barriers are removed, the possibility for greatly expanding the time spent on science in the elementary grades and for creating a synergy between science and literacy instruction is low."

Jacqueline Miller notes that: "E. O. Wilson proposes [in 2002] that science can be taught effectively through story. He states that the human brain functions by constructing narrative and that complicated, essential science can be communicated to a broad audience when presented as a story. The narrative can focus either on a historical period with scientists as the protagonists or on events that result from scientific phenomena."

Melissa Stewart makes the observation "that today's students are struggling with academic language did not surprise me. The nonfiction texts, including textbooks, that 21st-century students read are farther removed from academic texts than ever before. Most recent award-winning nonfiction trade books read like stories. The writing style is lively and engaging and often incorporates a variety of narrative elements. The design, format, and art in these books all work with the text to enrich the presentation... [use is made] of strong, active verbs and colorful phrases to grab the reader's attention. Students are encouraged to use a conversational tone and to let their voice, or personality, infiltrate their writing. These traits are diametrically opposed to the standard conventions of academic writing, which features complex sentence structure, a distanced, authoritative tone, and judicious use of passive verbs... academic writing [should] evolve to reflect the way 21st-century learners approach the world. Put another way, if academic writing were to become less formal and less terse, would the communication of scientific ideas suffer? I'm inclined to think that what matters is the writing process and the critical thinking it requires—not the language conventions used by the author".

As the national curriculum is developed particularly for the STEM subjects it will be interesting to follow how the designers and our federal and state governments cope with the matters raised above.