|

|

|

|

|

|

|

News & Views item - July 2009 |

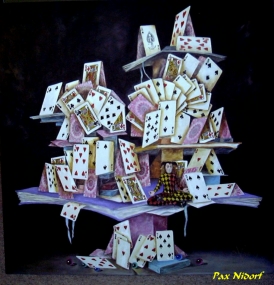

![]() Having Arrested the Disease What's Required for the Cure.

(July 1, 2009)

Having Arrested the Disease What's Required for the Cure.

(July 1, 2009)

Monash University's retiring vice-chancellor, Richard Larkins, was interviewed

by Andrew Trounson for The Australian's Higher Education Supplement and

voiced the sobering opinion that as welcome as the Rudd government's commitments to

restoring indexation and better covering the indirect costs of research are, the

measures aren't enough in the longer term. "What the Deputy Prime Minister in

the budget outlines is the arrest of a progressive decline in funding, which has

occurred over the last dozen years or so, rather than a substantial increase".

sobering opinion that as welcome as the Rudd government's commitments to

restoring indexation and better covering the indirect costs of research are, the

measures aren't enough in the longer term. "What the Deputy Prime Minister in

the budget outlines is the arrest of a progressive decline in funding, which has

occurred over the last dozen years or so, rather than a substantial increase".

Professor Larkins then continues: "I think by international standards the private contribution by Australian students is already high and that is why I say that given our current environment it would be better for the public funding to increase ... but it just seems unlikely, even in the out years, that the government will be able to do that or wish to do that... In that event I think the alternative of deregulating fees would be a better outcome provided it was accompanied by those equity requirements and measures... I think you can safeguard against it being a privileged environment for the rich. I think it can actually work in a reverse direction."

This sounds much like the system in place at private universities such as Harvard, Stanford and Princeton which have undertaken the policy of assuring that no student who meets the universities' entrance requirements will be prevented from attending because of need. If that's the case, it will require a remarkable financial juggling act by the Australian universities that attempt it.

Professor Larkins also told Mr Trounson "that in the long term Australia's economic prosperity will be put at risk if we don't begin to match the investment in education and research happening to the north of us in Asia. But he says it's a message that is still hard to get through in Australia, which he says has yet to fully shake the complacency nurtured by mineral wealth and the tariff barriers of the past. 'The current leaders in Canberra do recognise it and do speak about it a lot, but because of the global financial situation and partly because of other pressures they haven't yet made the quantum leap forward in investment that will allow us to be truly competitive'".

Meanwhile the president of the Australian Academy of Science, Kurt Lambeck, is warning that there is a critical lack of support for mid-career researchers, and notes that the budget's focus is on material infrastructure while human infrastructure still doesn't get a great deal of attention. Support for mid-career researchers is needed to ensure the next generation of university teachers and scientists. "We do need people in the future who can make effective use of the new state-of-the-art facilities [funded by the Super Science initiative]".

And University of Adelaide demographer Graeme Hugo told The Australian's Guy Healy that the shortage of highly skilled graduate technicians was increasingly being likened to the global shortage of peak researchers. "The pressure is coming not just from peak researchers, but key experienced people that back them up," Professor Hugo said, "This is problem seen as being on a par with the researchers and part of the talent war as countries and universities compete to attract the most skilled people."

Former Australian Chief Scientist, and current president of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering, Robin Batterham reinforced Professor Hugo's view saying: "When you put money on the table for super science - be it a survey ship, or a synchrotron or a square kilometre array telescope - it doesn't do anything for the operating costs such as the technicians to run them."

University of Sydney Australian Microscopy and Microanalysis Research Facility chief executive Simon Ringer told Mr Healy that the new funding for big-science equipment was "very exciting, but Australia needs brains as well as new stainless steel. There's a skills shortage of hundreds across the peak science infrastructure necessary for the (country's) infrastructure road map of the future. It may not sound like much, but it's a huge number of people given these are high-end specialists who will have a really important impact on Australia's global competitive position, to take us up the innovation rankings."

Finally, Australian Synchrotron director Robert Lamb said that he agreed with Professor Hugo's assessment, based upon his experience of staffing the country's largest and most complex scientific instrument.

Recently, Australia's current Chief Scientist, Penny Sackett, has described what she sees to be the role of the Prime Minister's Science, Innovation and Engineering Council, i.e. devising a long term roadmap. Professor Sackett's opening paragraph in her June 5 media release reads: "The Prime Ministerís Science, Engineering and Innovation Council (PMSEIC) met today to discuss how innovation, science and research can contribute to ensuring Australia is prepared for the challenges and opportunities of the future, which will involve new approaches to knowledge generation, health, sustainability, and economic and social development."

Well now, do we look to Professor Sackett and PMSEIC in anticipation, and more to the point will the Prime Minister, the Minister for Education, and the Minister for Innovation, Industry, Science and Research do so?